One of my favourite Thames finds is a bit of an oddity. It is quite modern and unlikely to be displayed at the Museum of London, but it carries its own promise of an interesting history. It is a small black pouch, with a rusty popper on the front. A heavy iron bolt has been carefully threaded through the back and tied down tightly. Tucked inside is a cassette tape, along with a slab of earthenware tile to act as further ballast. Whoever prepared this package wanted it to sink without trace.

A connection through the centuries

The banks of the River Thames at low tide can be an enchanting place to be. You are at the centre of one of the world’s greatest cities while at the same time quite apart, at a peaceful, otherworldly distance from the usual London bustle of people and traffic. In previous centuries, it was the city’s poorest residents who searched the banks of mud, pebbles and sand, looking for coal, rope or anything else that might be sold. Visitors today look for relics from the city’s past. Much of what a modern mudlark picks up has no more financial value than the lumps of coal collected by the city’s original mudlarks, but to those who search the river’s banks, each pottery sherd and clay pipe bowl is precious.

The historical finds that lie scattered across the foreshore represent a jumbled record of centuries of daily life in the city. Much of it has ended up there through accident or chance or has simply been dropped into the water without a second thought. Some items, though, have been placed into the river with a clearer intent, guided by myriad motives and emotions, everything from reverence, happiness and hope to anger, sadness and despair.

I find these deliberate deposits especially fascinating. They lie on the foreshore like a gift from the past solely because someone, decades, centuries or even millennia earlier, decided they belonged in the river where I now find them. A connection through the centuries. You put it down, I pick it up. They remind us that the Thames is more than waterway, defensive barrier, occasional dustbin and lost fishing ground. It serves a spiritual purpose in Londoners’ lives, whether we see it or not.

Some gifts are an expression of hope. Coins are thrown or dropped into the river like pennies into a fountain, accompanied by a wish for love, prosperity, health or whatever else the holder may feel is lacking. Discarded engagement and wedding rings, both modern and ancient, are often found close to bridges, consigned to the depths in a moment of hurt or dejection. Each is a reminder that people haven’t really changed. We are driven by the same fundamental desires and emotions as those who lived here before us.

Religious offerings are also a common find, many of them modern. The capital’s large Hindu population treat the flowing waters of the Thames as sacred and regularly place offerings into the river, everything from ceramic Diwali lamps and folded prayers bound with thread, to statues of Ganesh or Shiva and small lead yantras, even coconuts, painted or wrapped in cotton.1

The beliefs behind other offerings can be harder to establish. I found a little glass bottle on the Limehouse shore, neatly stitched into soft brown leather and with small, white conch shells added as detail. The bottle contained liquid but whether it was blood, urine, holy water or gin, I will never know.

Some things are consigned to the dark waters shrouded in quiet secrecy. One of the most intriguing instances is that of the Doves Press typeface. The Press was established in 1900 as a partnership between Thomas Cobden-Sanderson and Emery Walker. It attracted strong sales in its early years with editions of the King James Bible and Milton’s Paradise Lost, and its books were lauded for their Arts & Crafts aesthetic, distinctive font and ornamental initial letters. By 1906, however, the business was struggling and the two partners were at each other’s throats, wanting to part ways but locked in a dispute over the ownership of the celebrated font. In 1909, the two men reached an agreement: the older Cobden-Sanderson would retain exclusive use of the typeface until his death, after which ownership would transfer to Walker.

That was not what happened. Unable to accept that the beloved font would ever pass into the hands of the man he loathed, Cobden-Sanderson began a near-nightly routine in August 1916, walking under cover of darkness to Hammersmith Bridge and tipping a package of type into the river below. He made an estimated one hundred and seventy visits over the next five months, until the entire font, more than a tonne of letters, spaces, punctuation and other components lay at the bottom of the Thames. Hundreds of the little metal letters have been recovered in the century since, but only a tiny fraction of the many thousands dropped there. With each account I read, I vacillate between seeing Cobden-Sanderson as a passionate artist, protecting his cherished font from men who saw it only as a financial asset, and a selfish narcissist, guilty of cultural vandalism.2

A closer look

I inspected the Thames bundle more closely. The plastic casing of the cassette tape was cracked and damaged after its years in the river, and rust had corroded the screws and metal parts beneath the tape heads.

It is little wonder that cassettes evoke none of the nostalgia people feel for vinyl. They were certainly portable and allowed you to record from the radio or record player or through a microphone, but they were a lot of trouble too. The sound quality was often poor, and moving back or forth between songs was a guessing game, an imperfect calculation based on the assumed speed of the whirring cogs and the likely track length. The tape would sometimes shift as it spooled through until it got tighter and tighter against the cassette sides and either snapped or refused to move.

There was a bit of a DIY aspect to them. Certain players tended to chew the tape up, meaning it had to be carefully extricated, untangled and wound back into the cassette by hand, using a pencil to rotate the spool.

I decided to attempt a rescue. Prising open the casing as gently as I could, I removed the thin, coiled tape. The exposed section was inevitably lost to the rusted tape heads, but the rest seemed firm and intact, the edges dirty but the face of the tape still the usual coffee-brown colour.

I unwound it back and forth across a room to dry out, and then wound it all back onto the two spools, followed by a careful glue repair to join the ends and a new home in a different, clean cassette body.

I knew nothing of the contents, only that whatever was on the tape, someone wanted it gone. It had been disposed of like a body in a gangster film, packed inside a suitcase, weighed down with rocks and heaved over the side of a boat in the dead of night, far from the New Jersey shore.

Why would someone go to those lengths? What could warrant such efforts? I thought of the more exciting possibilities. A gangster’s confession, perhaps, or a covert recording of a crooked policeman. It is impressive, comical even, how far the mind can go when exploring a mystery like this, but not so surprising. The Thames has long been a favourite place to dispose of troublesome items, although in their haste people can forget that the river is tidal. I have learnt through the years that if you find a sock on the foreshore with its end tied, the contents are likely to be suspicious. I have previously found a black sock full of bullets and another with a gun inside, in a different location and on the opposite bank. It proved to be a starter’s pistol, but the means of disposal suggested it may have been used for something other than a school sports day.

I posted a photo of the cassette and weighted bundle on a Thames Mudlark Facebook group and received different suggestions on what to do. Take it to the police, one person said, and let the boys in Forensics uncover its shady secrets, maybe learn where the Kray twins had stashed all the money. Someone else pointed out that it was a very elaborate means of disposal. Easier to pull the tape out, scrunch it up and put it in the bin. Or simply record over it. Replace the damning contents with an hour of Duran Duran or Cyndi Lauper.

Pressing Play

I put the rehoused tape into the player and pressed Play. The machine gurgled its way noisily through ten, fifteen seconds of silence, and then, despite decades in the muddy river, sound came. It was garbled and uneven but I could make it out, nonetheless.

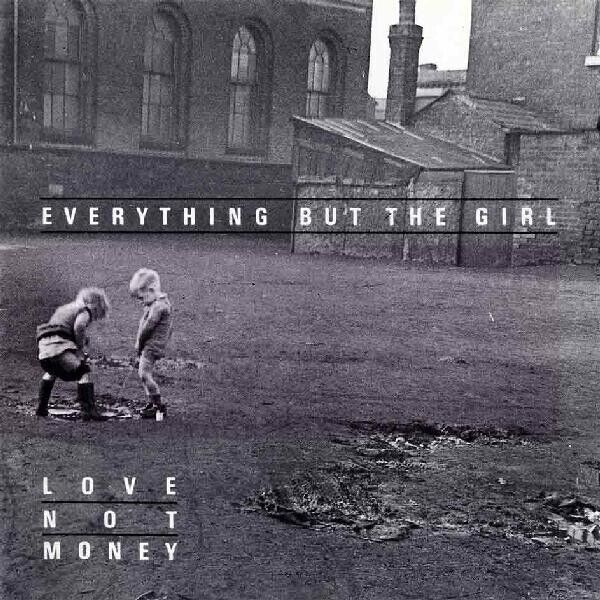

It wasn’t a long-lost recording of a crime syndicate discussing their next bank job, as I had quietly hoped. It was a mid-Eighties mix tape, consisting entirely of songs by the band Everything but the Girl, circa Idlewild and Love not Money.

The cassette had seemingly been banished to the depths not to destroy evidence of a crime but to destroy the memory of a former relationship. Whoever had made and gifted the mix tape had apparently done something so hurtful, so heinous and unforgivable, that more was needed than just to cry a little and move on. The scale of this betrayal demanded ceremony.

I see no other clues as to who was involved, but I picture a girl in her mid to late teens, angry and dejected, still pining for the boy she now wants to hate. Her best friend is with her, secretly enjoying the drama and relieved to be back in her friend’s life. She encourages her not to wallow and to find some kind of closure.

You don’t need him. You need to get him out of your head. You’re here crying and we know he’s not.

All that remains of him is this mix tape and a world full of painful memories. Together, the girl and her friend solemnly prepare the package in her bedroom, Morrissey and Suzanne Vega watching from the wall. The pair then walk together to the river, ready to bring an end to the whole sorry episode.

Throw it as far out as you can. Forget him.

The girl takes a deep breath, braces herself for a future without the toxic presence of her now ex-boyfriend, and heaves the bundle as far out into the river as she is able.

This mix tape represents everything you ever meant to me.

I am banishing your memory to the dark waters and cold mud.

Fuck our stupid relationship.

Fuck your stupid mix tape.

Fuck Everything but the Girl.

But most of all, fuck you.

I date the music to about 1987 and suspect that the tape’s owner was in his or her mid to late teens when they threw the bundle into the river. If so, then they were likely born in around 1970 and might now be between 50 and 55 years old. Was it you?

Endnotes

- For more on the Thames in Hindu religious rituals, read Jason Sandy’s excellent 2019 article ‘Mudlarking: Modern Sacred River’ in Beach Combing magazine (https://www.beachcombingmagazine.com/blogs/news/mudlarking-modern-sacred-river).

- This account of the Doves Press typeface is based in part on information from the website for Emery Walker’s House (https://www.emerywalker.org.uk/doves-press) and an account on Typespec regarding Robert Green’s creation of a digital facsimile (https://typespec.co.uk/doves-type-revival). Image: Hindman Auctions.

Note: Everyone is free to walk along the tidal Thames foreshore, however anyone wishing to search its banks in any way for any reason must hold a current foreshore permit from the Port of London Authority (PLA).